A decade ago, it was difficult to understand when things were good and bad in the financial markets – even as the world struggled to recover after the Great Recession of 2008, house prices and stocks and bonds just kept climbing. However, what could be seen as good news, such as wages starting to rise, could cause the market to stir. This was due to uncertainty over central banks raising interest rates.

But when COVID-19 hit, there wasn’t the same ambiguity – absolutely everything fell. The global stock market completely tanked in March to an all-time low, and even American Treasury bonds, which are considered to be the world’s safest asset, fell in price. However, the Federal reserve then cut the interest rates and provided liquidity to the market to avoid a credit crunch and mass bankruptcy. Other central banks then followed – since January, Britain, Japan and Europe have now created $3.8trn of new money.

The markets took a surprising turn; gloomy forecasts were completely wrong and between April-August, the global stock markets rose by 37% largely due to the rise in technology shares. There was a record issuance of America’s corporate bonds in the first half of the year and many housing markets saw a great increase. Average house prices in Sydney in August were 10% higher than they were last year and Britain’s house prices are at an all-time high.

The “natural rate of interest”

Before COVID-19, the central banks were already being accused of keeping deadbeat firms alive, causing more wealth inequality and making house prices just not affordable for young renters, even during periods of weak economic growth. Now that the pandemic has hit, these monetary policy side-effects have just got worse in a very short space of time. This is not necessarily the fault of the central banks, as they need to do something to respond to the current economic conditions.

For decades, interest rates have been heading downwards as the central banks have been responding to shocks to the economy. But the fact that this monetary stimulus has not provoked any major inflation to consumer prices demonstrates that the central banks are not distorting the market forces, just reacting to them. It’s simply just a case that the global interest in saving has exceeded that of investing.

While interest rates are low, the maths around discounting means that future income, and therefore assets, are more valuable. In a recent paper by David Delle Monache of the Bank of Italy, Ivan Petrella of Warwick University and Fabrizio Venditti of the ECB, they find that the decline in the “natural” interest rate can actually explain most of the rise of dividends prices in America’s financial markets dating all the way back to the 1950s. This “natural” rate of interest balances saving and investment without causing unsustainable booms or recessions.

The pandemic is not the only thing to impact the natural interest rate – the 30-year interest rate in America has fallen almost a percentage point since January, which fits the historical pattern. In a recent paper by Òscar Jordà of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, and Sanjay Singh and Alan Taylor, both of the University of California, Davis, they study 19 different pandemics that have occurred since the 14th century and they found that interest rates have been suppressed long afterwards, even after the financial crises. They estimate that 20 years after a pandemic, the interest rates are roughly 1.5% lower than they should be. COVID-19 is not quite comparable to episodes such as the Black Death and the Spanish flu, as they killed many young workers. But even half as large an effect would have a significant impact, considering how low the interest rates were already.

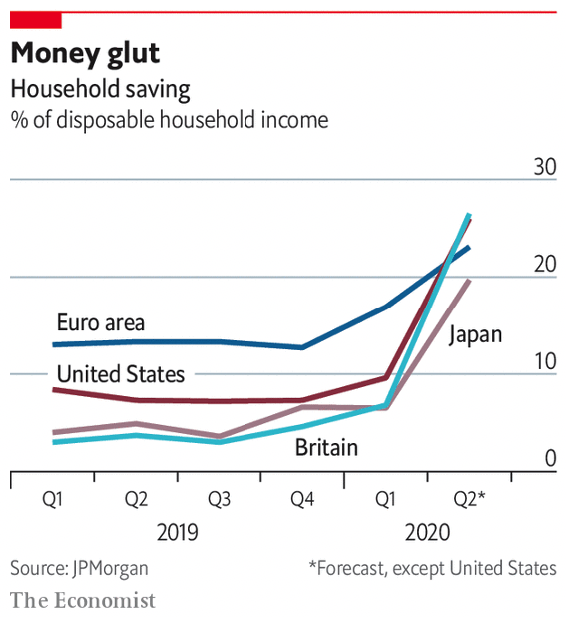

However, COVID-19 is strengthening the structural forces that are pulling down the interest rates in many ways. One way is because households and firms are now much keener on saving hordes of cash. Since economies have been locked down and it’s harder to spend, saving rates have surged. Some predict that these larger bank balances of consumers mean an impending inflation, but the likelihood is that there will be a prolonged period of “precautionary” saving, which is pretty standard after recessions.

Pandemic-driven rates

This is not your typical recession – it revolves much more around risk. Economists for years have been suspecting that the risk of disasters weights on interest rates. Some were even saying that it explains the “equity premium puzzle” – the gap between the safe interest rates and the returns from shares.

In a recent paper called “The long-term belief-scarring effects of COVID-19”, Julian Kozlowski of the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, Laura Veldkamp of Columbia University and Venky Venkateswaran of NYU Stern explore the beliefs about risk and estimate that it might depress the natural interest rate by two-thirds of a percentage point. “Whatever you think will happen over the next year,” they write, “the ultimate costs of this pandemic are much larger than your short-run calculations suggest.”

Another way in which COVID-19 can depress the natural interest rate is by boosting income inequality. Before COVID, many economists argued that because the rich save a higher proportion of income compared to the poor, this led to high rates of income inequality in the “rich” countries such as America. The higher rates in these countries has then contributed to the decline in the natural interest rate over decades.

In a paper by Adrien Auclert of Stanford University and Matthew Rognlie of Northwestern University, they find that nearly 20% of the decline of the natural interest rate since 1980 is due to rising inequality. COVID-19 could end up compounding this effect if it continues to leave the labour markets unbalanced.

The massive rise in government debt is a force against this, however. The low interest rates and weak growth can be attributed to the shortage of safe assets to absorb the world’s savings, for example. But the pandemic has seen the government issue a ton of debt to fund emergency spending. In June, the IMF predicted that the global public debt would rise from a weighted average of 83% of GDP in 2019 to 103% in 2021. The EU plans to issue €750bn of joint debt – so COVID-19 has seen the creation of a new safe asset. This new debt should soak up savings, in theory, which should help raise the natural interest rate.

What is the effect of low interest rates?

Low interest rates generally mean it’s easier for politicians to react to demands from the public – such as spending more on healthcare, pensions and fighting climate change. However, they also leave governments vulnerable to increasing interest rates, should they come back. During the pandemic, central banks and the governments have been working together to combat this, but what happens if their goals suddenly diverge?

Low interest rates would also mean that high asset prices are all but guaranteed. This will therefore reinforce the grievances about wealth inequality. There’s been a clearly unequal distribution of job losses this year and homeowners, who are generally in professional vocations have been largely unaffected compared to the service-based professions. One of the reasons why the housing market is doing well is because the downturn is not hitting your typical house-hunter. Instead, homeowners can benefit and take advantage of cheaper mortgages – those who are less wealthy or do not have access to finance will feel understandably left out.

The most significant issue is that central banks have been stripped of their main response to fighting recessions – cutting short-term interest rates. With them being so close to zero already, they have little options left. Even buying bonds from the central banks is less important now due to the ridiculously low interest rates. Monetary policy can’t do much now apart from stop the long-term rates from rising. The recovery will rely on the government to provide an adequate enough fiscal response. The Federal Reserve recently promised to allow inflation to overshoot its 2% target while the economy is recovering. However, this will only take effect if the fiscal stimulus causes more inflationary conditions.

The overarching problem of low interest rates is how fragile the economy is and how much harder it will be to fight recessions. Investors will find it more difficult to hedge risk and bond prices cannot increase any further with yields near zero. High asset prices accompanied by the drastic income equality then threatens the social contract. With all this in mind, economic policy needs a serious review.